Inside A Banjo Player’s Mind

An Interview with Bela Fleck

I spent an afternoon in 1995 talking with banjo master Bela Fleck about his creative process; this interview first appeared in Acoustic Music Magazine in August of that year. Looking back, I realize the extent to which Bela planned the direction of his music and career early and followed his instincts. Here is a man who knows what he wants.

CL: Tell me about your music, the heart of it all – composition, technique – how you got to where you are, basically…

BF: Music and Art High School in New York. When I was in high school, I got exposed to a lot of really great music that affected what I wanted to do. I heard bluegrass and I liked it, although the singing put me off at first. I also heard jazz and classical and all this other stuff. When I was learning to play bluegrass, I was also learning what I could pick up off everything.

I found that if I brought my banjo and played bluegrass in front of my high school, that wouldn’t attract as much attention as if I played the blues or if I tried to play a Yes song or a Led Zeppelin song on the banjo or even a Beatles song – those kids up in New York would relate to that a lot more. Some people thought I was pretty strange to be playing bluegrass. So all that affected the music that I started writing.

. . . the Flecktones sounded unusual not just because

they have the banjo and the music but because a lot of the music is being seen through a banjo player’s mind.”— Bela Fleck

I really didn’t start writing until I had been playing banjo about three years. I wasn’t very serious about it. I didn’t have the confidence that I would write anything worthwhile; I was just fooling around with the banjo. I remember when I was in Tasty Licks in Boston. Jack Tottle (mandolinist with the band Tasty Licks) told me he thought I should try to write; he thought I might have good luck with it.

I tried to be more serious about it and things would pop out. I was only interested in it if things were pretty weird, pretty complex. At that time, I wasn’t interested in coming out with anything traditional. But as time went on, and I got more interested in bluegrass itself, I found I wanted to write tunes that could be traditional as well, that might sound like a Bill Monroe tune or a Norman Blake thing or different style of bluegrass or different styles of acoustic music.

Ricky Simpkins, Bela Fleck, Tim O’Brien, Mark Schatz, Jerry Douglas, Russ Barenberg, Ryman Bluegrass Series, 1994

I got to where I wanted to be able to write something that sounded like a string quartet or something that sounded like like an Irish tune or something that sounded like a Charlie Parker tune or a Chick Corea tune. I found that I was trying to write all these different tunes in different styles, but the stuff I was doing that I was most interested in were the tunes that didn’t seem to be in any particular style; I really couldn’t say what it was. I was very banjo-oriented. It was based around the tuning, the picks and the notes that would become available, the open strings and stuff. That stuff started really jumping out to me as being a little bit different, as an area I should continue.

The writing developed over the years. I did seven records on Rounder and five now on Warner Brothers. They are almost entirely self-written, so there is a lot of material out there. I keep trying not to write the same pieces over and over again, with different chords or different forms, but keep trying to learn new things as I am writing. Usually the writing is the furthest edge of what I can just barely do, or I write the hardest thing I can play or I write things with harmonic information that I haven’t used before.

Bela Fleck, Mark Hembree, Pat Enright, Roland White, Kathy Chiavola, Gene Wooten, jamming at the Station Inn

For instance, you might teach a songwriter a new chord they didn’t know, and they find a way to incorporate that chord into their next song. Well, I’d be that way. I might find a voicing or something and really like the dissonance of this voicing but not know how to use it. So I would write a piece around it and try to expand that dissonance or expand that technique so that it would teach me something about the instrument, as well as yielding something unusual.

. . . The banjo is so interesting because, in a way,

it is somewhat limited by the picks, steel strings, and that percussion of syncopation that only a banjo has. In one way it limits you but in other ways it allows you to go into very strange areas because of that sound.”— Bela Fleck

I figure I have a banjo player’s mind at this point. I’ve been playing for 20 – something years (in 1995) and if I were to write something typically jazz, it would come through my banjo player’s mind and it would come through the instrument so that, even if I took that piece and taught it to a saxophone player, it would sound different than other jazz because it came from the banjo, I think.

So, in that way, the Flecktones sounded unusual not just because they have the banjo and the music but because a lot of the music is being seen through a banjo player’s mind. I don’t know how else to put it. You might say the same thing about Bill Monroe. His band is seen through a mandolin player’s perspective, or maybe Duke Ellington’s band was seen through a pianist’s perspective. So I think it yielded some unusual things just due to the way things fell, me playing a banjo in this different way.

Sometimes I would write something and get Howard (Levy) to play it on the piano. It would sound real unusual on a very conventional instrument.

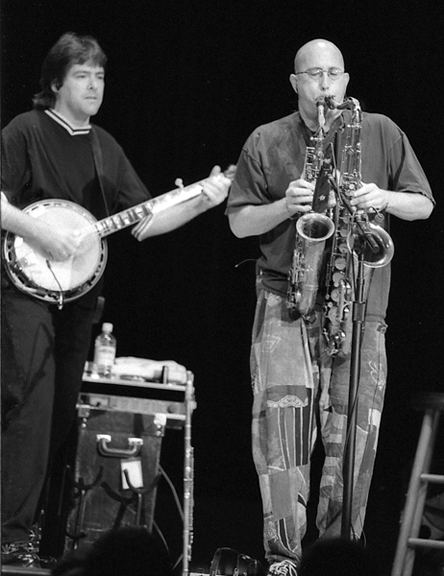

(Photo left: Bela Fleck and Howard Levy)

The same thing happens when I learn a saxophone melody or a piano line or clusters of chords or something from a jazz artist. It sounds different on the banjo. It occupies a different mental space because it’s not coming from a banjo player’s mind. So all those interesting juxtapositions come in when you do that.

Victor Wooten always said that the most inspiring thing he can do is hand the bass to someone who doesn’t play bass and see what they do. I think it’s a good approach. That’s just one part of it.

CL: So this is an instrument–oriented music, rather than, say a Mozart piece composed for all of the orchestra instruments. You compose for banjo and everything else goes through that. How did your music fit with the Oriental music you were exposed to on your recent trip to Outer Mongolia and China?

BF: They have all kinds of instruments there. They have instruments that look and sound like banjos but without frets. I’m thinking of Mongolia right now, and Korea. They have an instrument that sounds like a fretless gut-stringed banjo. And the music they play on it is similar to what you might hear in Appalachia. I think there’s a lot of interesting mountain-sounding music over there I could relate to that way. I learned some Korean music, and it was very difficult because of the bends. They bend so many notes, and for a while I was bending every note I was playing, just to try it on for size. It’s a lot of work but it’s a really interesting sound, very Oriental.

They have songs in the conventional scale that we are used to, and then they have pieces in their scale, a scale that is divided into several equal parts. In Indonesia and Thailand, it sounds kind of tribal, different, to us. It doesn’t sound bad in that context. The only thing that sounds bad is if you try to play the scale we are used to along with it. Then they clash by semitones; that doesn’t work too well.

But we played with those musicians and found ways to play things. I would try to bend strings to get in between notes where I could and, other times, just let the dissonances happen and not worry about it. When you are playing with people who are just playing percussion it is no problem. It’s when you get to the harmonic world that different scales become an issue. But, rhythmically, we had some great jams with people in the Philippines and Thailand.

CL: On musical experiences encountered on the recent Far East trip, what are the similarities?

BF: The only thing harmonically consistent is the octave. That seems to be a natural thing for people to hear the same notes an octave higher. Most countries do more with semitones than we do: India, China, the Far East, Middle East, Africa. In every country we played with musicians and we were able to find common ground. We would get them up on stage; it would be the favorite part of the night for the audience. It was the thing I was most excited about.

When we’d get into each country, I would look for tunes that we could learn that I liked. There was a lot of stuff that I was unsure I could relate to, but inevitably, two or three tunes would pop out, or I’d ask someone to sing a song from their country and I’d tape it. That night we would play it on stage. It was really beautiful, a cultural interaction. That has always been one of my favorite things.

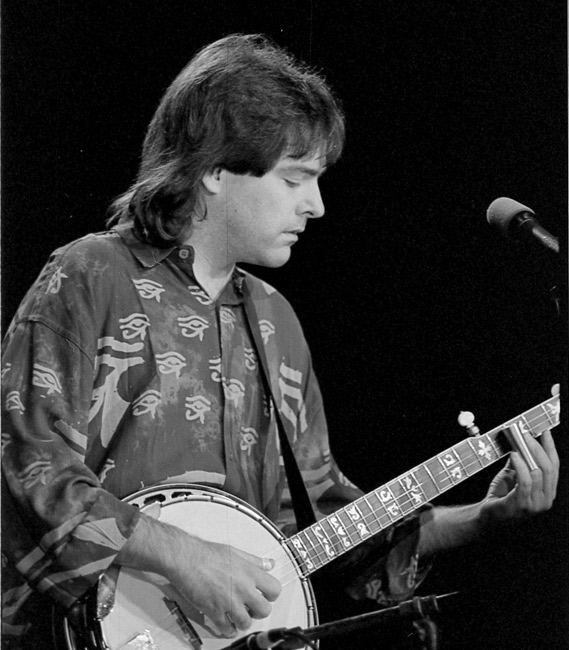

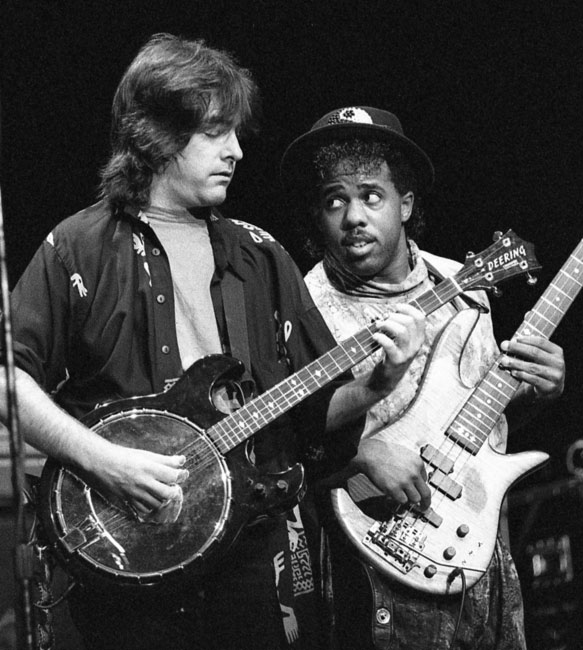

Bela Fleck, Sam Bush, John Cowan, Pat Flynn of Newgrass Revival.

Newgrass Revival did two trips, one to India and Africa and one to Portugal, Spain, Greece, Malta, Turkey. On both of these trips I really thrived on learning the songs and hearing the musicians. I brought back a lot of ideas. In this trip with the Flecktones, the guys were just as eager as I was to soak it up and get ideas and learn. We wanted to come back having gotten something out of the trip. We came back with eight or 10 songs that we will play now. It is really cool.

CL: How do you view your band development from Newgrass to the Flecktones?

BF: Newgrass Revival was a great thing for me to be a part of for my own personal evolution. We were together eight and a half years. I think we learned a lot from each other. Eventually, there were a lot of things I wanted to do that just weren’t appropriate for Newgrass.

I started to feel the need to do other things. I started jamming them in between Newgrass tours. Newgrass worked a lot, and when I came home I would try to do things: produce people, put together my own band, play on a hardcore bluegrass thing. The Dreadful Snakes came together partly because I wanted to play bluegrass as well as Newgrass. I was making records and trying to pull all these musicians like Sam (Bush) and Jerry (Douglas) with me and do what I wanted to do. I hadn’t really found the thing. I was working all the time with Newgrass Revival and coming home, filling every spare moment with something to try to feel whole.

Dreadful Snakes Blaine Sprouse, Bela Fleck, Mark Hembree, Pat Enright, Roland White. Not pictured: Jerry Douglas.

The Flecktone thing just kind of fell into my lap. I realized I was at a crossroads and if I didn’t do this, I would always look back and say, “there was your opportunity.” I was forced to make that move (to leave Newgrass Revival) even though it was a really hard one for me to make. It’s kind like getting a divorce. Also, being the guy to say, “Okay, the ride is over. It’s not going to be like this anymore.” I remember lying awake–that was the dark side of it. The very positive side of it was I was so excited about this music. I was finally doing all of the things that I wanted to do in one bundle.

CL: So the Flecktones eventually evolved into a quartet with Victor Wooten, Future Man and Howard Levy…

BF: I found these musicians who were just like me, into stretching and trying everything. Suddenly, instead of trying to simplify, I would pull out the most complicated things I had ever written and throw it to them. I was actually being challenged to write difficult music for the first time in my life, not the reverse, not “You gotta make it dumb.” In Newgrass we were getting a lot of pressure to “Keep it simple, stupid” for country radio. We resisted that quite a bit.

I was also inspired by Newgrass Revival, who built their own audience. We had a sizable cult audience at the time we broke up, a very powerful audience that had nothing to do with ‘commerciality’ or country music. It had to do with a band that was together 17 or 18 years, just sticking to it’s own vision. When I left Newgrass, I thought, “It may take me five or six years before I even make a living again, but if I just do what I want to do–not what someone else wants me to do–then eventually I’ll have some sort of fan base. People will support it hopefully, and I’ll get to do this the rest of my life – which was my goal. . .” Oddly enough, it blew up, all this stuff started happening: We made a video, we were on TV, we were getting Johnny Carson, things like that.

Mark O’Connor, Bela Fleck, Vince Gill, Sam Bush, Ricky Skaggs, John Cowan, Pat Flynn, Famine Relief Concert, 1985

Suddenly, we all thought it would be the next big thing for a while. It was boom time for us. We sold a lot of records. The thing just went. We were being booked at major jazz festivals. Our first concert in New York was with Stevie Wonder and Take Six. We were on the Take Six tour and Bonnie Raitt’s European tour. It was just cookin’. We made a second record and it went great. We made a third record and it went real strong. By staying together we built our own little business, our own little world.

Around that time Howard started reaching the same place I had been with Newgrass. Three years had gone by and he had other things he wanted to do. Howard is a guy who can walk in and play 50 instruments, play anything. People said they weren’t surprised when he left; they were surprised he had stayed so long. I feel really glad he was with us and I’m really glad he left when it was time.

That was a frightening time; I was afraid everything would fall apart. The direction came from Future Man, who said, “I think we should be a trio.” We had been a trio before Howard played with us. We sat down in my back room for a month. I got out this new instrument which was a banjo Crossfire with a MIDI guitar pickup attached – which was giving me a lot of new sounds. Future Man was expanding his whole thing. Victor was prepared to play two basses and he had his cello. We were prepared to do anything.

So we just went to work and we started playing gigs. It was scary for a while, but it’s fine. Our audience has grown over the last two years since we’ve been a trio. It grew, and we all got a lot stronger as musicians. I always felt Victor, Future Man and I made a great rhythm section for someone else to play on top of. That didn’t happen anymore; it became always two people backing up one. We tried to make it into good-sounding music, and that’s what we did.

(Photo left: Bela Fleck and Victor Wooten)

Victor recorded a solo bass album in late 1994 with all this great stuff he has. I thought this would be a good time to do an album on my own, pull Sam and Jerry and some of the old guys together. For a while I thought it would be a Drive-type record. The more I thought about it, I felt I wanted to do this record with Victor and Future Man, and I wanted Tony Rice to see what it is like to play with them, Sam and Jerry. I wanted to bring all these worlds together and make it real acoustic.

A few things happened that kicked the record into a more interesting place still. Through Victor, I was talking to Ron Moss who manages Chick Corea. He encouraged me to call Chick and gave me his home phone number. We had a great conversation, and he said he’d love to play on the album. I saw the concept changing, but since piano is an acoustic instrument, I thought it might all hold together. I wanted bassist Edgar Meyer as well. Victor and Edgar still ended up playing basses together. It never sounded strange; it just worked. Edgar, Chick and I did a trio.

Since we already had Chick and the Flecktones in L.A. to record, I called Branford Marsalis, just on a fluke to see if he would be interested in coming in. He had never played with Chick and he said sure. When you’re playing with people you never play with, there’s a certain energy. You’re learning the songs on the spot, and everyone just goes for it. There’s a moment of discovery that happens.

Sam Bush, Stuart Duncan, Tony Rice, Bela, Mark Schatz, Mark O’Conner, Jerry Douglas

The record was starting to take on all this different breadth. We had Stuart Duncan and Jerry Douglas, Edgar – the Strength in Numbers kind of acoustic thing – then Tony Rice adding some great things, like he might have done in the Grisman Group or the early Tony Rice Unit, when he was playing some really beautiful melodies and chording on the guitar. It worked great. I was talking to Bruce Hornsby who played on my last record. I needed to get him together with Tony Rice because I thought it would work. Bruce has a bluegrass sensibility, actually.

The record just turned into a mass acoustic experience. Future Man actually developed a percussion kit for this, which was banjos. We were at Gruhn’s (Gruhn Guitars, Nashville) and Future Man started playing percussion on the big-head banjo that was laying on the counter. It sounded like tablas – he was playing the strings with his fingernails. We bought a couple of old banjos and he made them into a kit. A lot of the percussion on the record is Future Man playing the banjos with brushes, a very unique approach. Something is pulling the track along in a really nice way, and it’s often just his fingers on the banjo head. (Photo below: Future Man)

CL: What about Future Man’s Drumitar?

BF: The Drumitar is Future Man’s creation from an idea he’s had for a long time. We visited his parents’ house in Virginia, and there’s a Fender guitar with a drum machine nailed to it. That must have been the first Drumitar®, built by Future Man as a child.

He thinks there’s a way to get away from the physical side of drumming and make it more of an emotional thing. He wanted to put the drum under his fingers: hand drums. He could see that you can do more than just play the drums; you can paint all different kinds of colors. And as time has gone by he’s had access to more and more sounds, possibilities.

In simple terms, they are these little piezo pickups and, when you tap them, they send a signal to a drum machine, a snare or some other drum, a highhat. He has maybe 50 or 60 on his Drumitar®, hooked up in series to do different things.

This year we have been touring with the guests on our record, starting with Sam Bush going out with us in March; Paul McCandliss in April; and in May in Nashville with Paul, Sam, Edgar, Jerry, Stuart and Chick; and one in Louisville with Bruce Hornsby. Working with Victor, Future Man, Zack Newton (our stage manager) and Richard Battaglia (road manager and sound man) is a great team and it has really worked well. Richard is our other partner; he takes great care of us and makes us sound real good.

Written by Charmaine Lanham and published in Acoustic Musician Magazine, Summer, 1995; republished January 30, 2013 by Dancing Noodle Magazine.